Copyright Information

What is copyright?

It is a form of protection provided by the laws of the United States to the authors of “original works of authorship,” including literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, and certain other intellectual works (Copyright Basics 1). Copyright is automatically applied when the work is created and “fixed in a copy” in some format (e.g. paper, film, audio, etc.), even if it does not mention or list the © symbol or the word “copyright” (Copyright Basics 5). Title 17 of the United States Code encompasses copyright law.

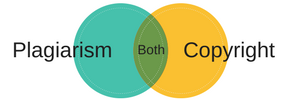

Note that plagiarism is a separate issue from copyright infringement. It is possible to plagiarize a source without infringing on copyright, and vice versa. For example, if a student copies and submits a chapter of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice (a public domain work) for an assignment, they have plagiarized but not broken copyright law. On the other hand, if that student uploaded the 2005 film adaptation to YouTube, noting that the movie belongs to Working Title Films and StudioCanal, the writers, the producers, and so on, they have not plagiarized the movie (they gave credit to the creators) but they have infringed the copyright (by duplicating and distributing an unauthorized copy of the work).

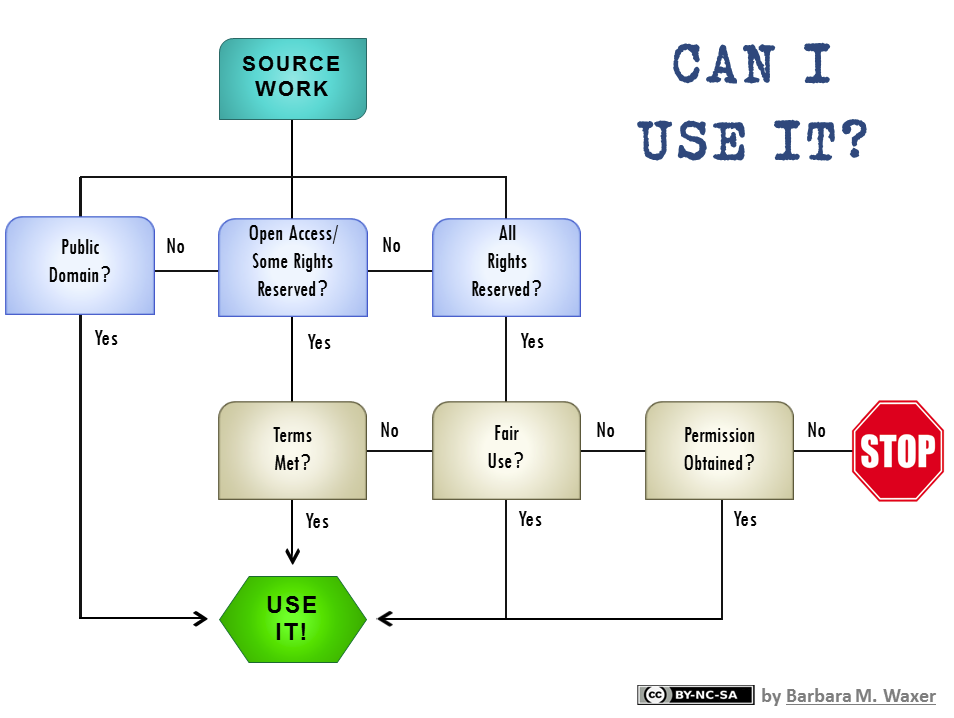

It can be frustrating and confusing to figure out what you can use and how, as there are no specific quantities for how many pictures or what length of video or audio you can borrow established by copyright law.* Educational uses are typically favored, but this factor alone is not enough to guarantee you’re good to go; neither is simply giving credit to the original creator.

Some works, particularly digital media, may also come with license terms and conditions that can limit or expand what you can do with the content beyond what copyright law says. Often you have agreed to the terms simply by using the content. Library-licensed content available through our databases is a good place to look for more permissive licensing; the Creative Commons is another example (explained further down the page).

Requesting permission from the copyright owner is another good option, but this process can be hampered by determining who the owner actually is, how to contact them, and waiting for a response. Many times the permission comes with a price tag, as well.

Fortunately, copyright law has provisions for “fair use” exceptions (among others) that let you use portions of works without having to ask for permission. You may freely use public domain works however you choose.

* You may come across guidelines suggesting, for example, “no more than 10% or 3 minutes of a film” or “a maximum of 30 seconds of a song.” These recommendations derive from a set of guidelines that attempt to establish conservative but definite figures for usage. However, these recommendations are not legally binding and are not part of copyright law (Crews 77-79). Actual permissible uses (fair use) may, depending on situation, greatly exceed those guidelines.

Fair use is a set of exceptions built in to copyright law that enables people to make limited use of copyrighted materials without having to request permission. Fair use is always determined on a case-by-case basis by weighing all four factors against each other. No single factor is more important than any others.

The U.S. courts use the following criteria to determine fair use (“U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use”; Crews):

- Purpose and character of the use

- Is your use commercial or for nonprofit educational purposes? Is your use transformative, i.e. are you creating something original and different or using the work in a new way? (Crews 59-61)

- Nature of the copyrighted work

- Nonfiction works are favored over fictional, dramatic works for fair use evaluation. “Consumable” works, like student workbooks or lab manuals that are meant to be filled in by individuals and repurchased, are less likely to be fair. (Crews 61-2)

- Amount and substantiality of copyrighted work used

- Amount is straightforward: how much of a work are you using? Short excerpts are more likely to be fair than longer ones. The aspect of substantiality is more qualitative, however: you might have a short quote but if it’s from the “heart of the work,” the key, unique, significant section, you start moving out of fair use. (Crews 63-4)

- Effect of use upon the potential markets

- Does your use undercut the licensed uses of the work? Will your usage discourage sales of the original material by serving as a reasonable substitute? Maybe the copyright holder doesn’t offer something like your derivative creation, but your use might still impede their market share someday. (Crews 64-6)

Any work with no copyright protection is labeled as public domain and is available for anyone to use with no restrictions. Works published before 1928 as well as government documents are in the public domain. A work whose copyright has lapsed also becomes part of the public domain. Works may also be deliberately placed in the public domain by the creator. ("Welcome")

Just because a work is publicly available does not mean it is in the legal public domain. Similarly, if a work is no longer actively being published or is not easily purchased does not mean it is no longer protected under copyright.

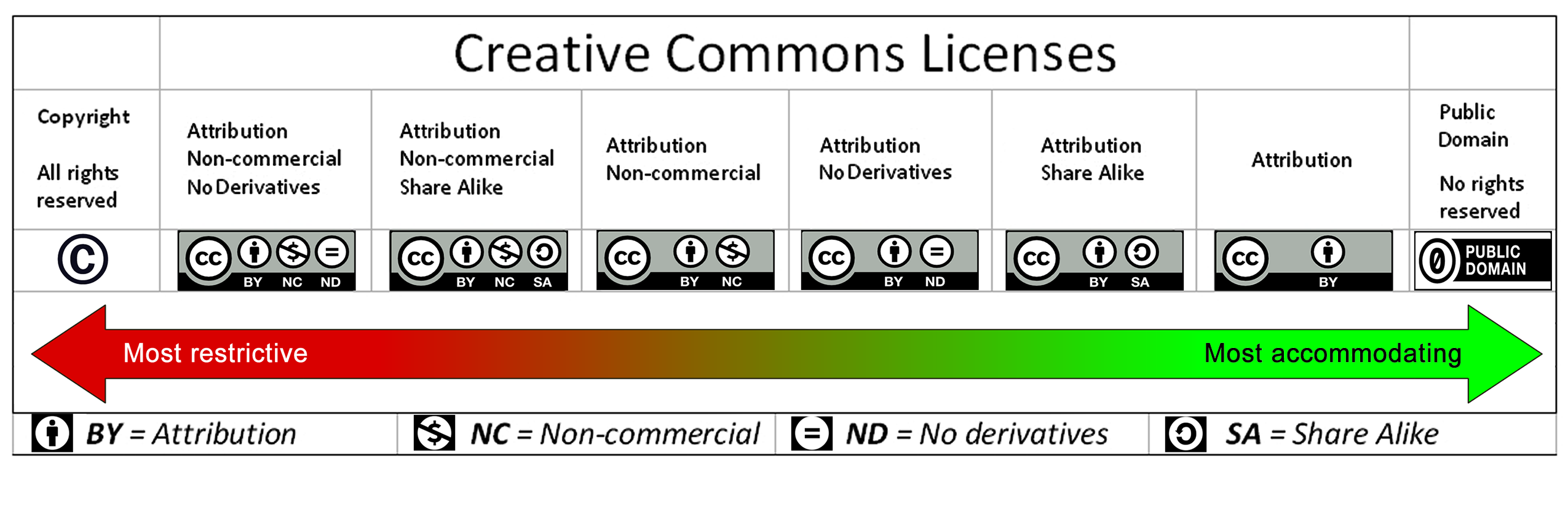

The Creative Commons refers to a set of pre-written licenses designed for content creators to explicitly make their works available for use and modification. It does not replace copyright law and CC-licensed works are still copyrighted, but the terms provide more flexibility to creators who don’t want “all rights reserved” (“About the Licenses”). You will typically be able to recognize these types of works by the license icon which lets you know what conditions you need to meet to be able to reuse the work. You will see CC-BY at a minimum, meaning you can do anything with the work so long as you provide attribution to the creator.

Creative Commons Licenses image CC-BY Barbara Waxer

You shouldn't think of copyrighted images, music, etc any differently than you do the articles (which are also copyrighted!) you use to get information. Anything not original to you should be cited (credit given to the creator), and you should not use others' works excessively (i.e. limit how much you use).

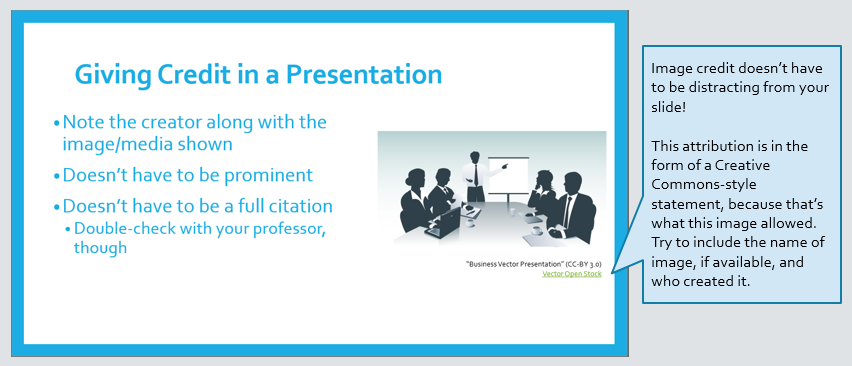

Informal Attribution:

Due to the visual nature of presentations, you'll probably have various decorative elements that aren't part of your information sources. Ask your professor for their preferences but generally these don't need to be formally included in your Works Cited list with your actual sources. Add attribution on the same slide as the images, etc. that you’ve used. It should be visible and readable, but it doesn’t have to be prominent (see image below for example). If there is a Creative Commons (CC) license, use that; if not, you can get by with a simple note like “Image by [author]” with a hyperlink to your source.

Formal Attribution:

Just as you would in a written essay, all information and concepts you found from another source should be documented with in-text citations where you actually use the ideas and an accompanying Works Cited list at the end of your presentation on its own slide or two. Ask your professor for their preferences if they want you to write formal citations following an official citation style for the multimedia resources you use. Remember, however, if you got information for your project from any source regardless of medium, you must cite it!

Images

- MorgueFile (public domain stock photography)

- Flickr Commons (historic photography)

- StockVault (free stock photos)

- Pixabay (public domain stock photos and illustrations)

- Canva (free online graphic design tool that includes a selection of free stock illustrations)

Audio

- FreeSound (CC-licensed sound effects)

- Audionautix (CC-licensed music)

- Free Music Archive (CC-licensed music)

- "About the Licenses." Creative Commons, creativecommons.org/licenses.

- Copyright Basics. Copyright.gov, United States Copyright Office, 2012, www.copyright.gov/circs/circ01.pdf.

- Crews, Kenneth D. Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies & Practical Solutions. 4rd ed., ALA Editions, 2020. Read the e-book from LSC Libraries.

- "U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index." Copyright.gov, United States Copyright Office, August 2025, www.copyright.gov/fair-use/.

- “Welcome to the Public Domain.” Copyright & Fair Use, Stanford University Libraries, fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/public-domain/welcome.

- LSCS Copyright Policy

- Citation Help

- Harper, Georgia. Copyright Crash Course. The University of Texas Libraries, 2024, http://doi.org/10.15781/T24J09X6J.

- US Code Title 17: Copyrights (full text of the law)

Disclaimer: The material on this page is for general information only and should not be construed as legal advice.